Resilience has been one of the buzzwords of 2022. Every organisation proclaims that they must be resilient in these times of climate change, pandemics and geopolitical instability. Google Trends also shows that the term ‘resilience’ has become 4 times more popular in the last 10 years. But what exactly is resilience and what does the term mean for organisations and companies? Can we measure it and can organisations work on ‘being more resilient’? Is a resilient organisation also a high-performance organisation? These are the questions we have been asking ourselves at PM for the past 2 years, and our research some interesting insights.

First, resilience in itself is not a characteristic of an organisation but rather the result of various other capacities or characteristics of that organisation. We make a simplified analogy with the decathlon. A decathlon consists of 10 different athletics disciplines. For each discipline, the athletes receive a certain amount of points, depending on their performance. After the last discipline, the athlete with the highest points total wins. Therefore, an athlete cannot be good at the decathlon in itself. Similarly, we argue that an organisation cannot be described as resilient in itself. A better description would thus be that organisations score well (or poorly) on certain capabilities that contribute to dynamic resilience.

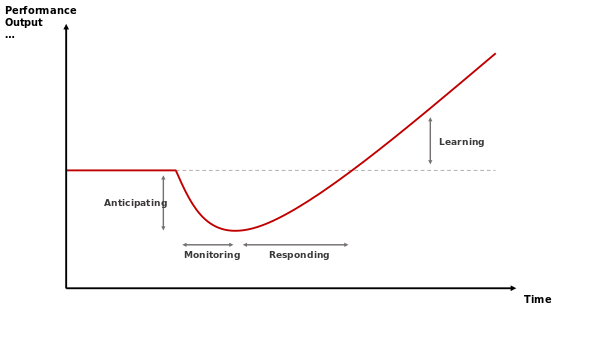

We realise this statement raises more questions than it answers. What exactly are those capacities that contribute to resilience? Can we measure them and can organisations improve them internally? To understand this, we focus on the only moment where resilience (or the lack thereof) can be experienced: in times of disruption. The image below shows how a high-performing system such as a well-functioning organisation or company faces a disruptive event. Using this simplified representation, we can derive 4 basic factors that contribute to the integral dynamic resilience of an organisation:

- How well an organisation can anticipate events will determine how great the impact on system performance will be.

- When an organisation is able to monitor the right factors, it is able to react at the right time.

- How well an organisation can react and coordinate its response will determine how much time is needed to get back to its usual output.

- Finally, organisations that are able to learn from events will be able to create a bouncing-forward effect.

Using these 4 factors, we can not only estimate how resilient an organisation can be in face of disruptive events, understanding how exactly they contribute to resilience also allows them to build on these factors. Just like an athlete cannot train for the decathlon itself, an organisation by definition cannot build resilience. It can, however, work on these 4 factors in the same way that an athlete can train for individual disciplines in the decathlon.

Finally, the question remains whether a resilient organisation is therefore also a high-performance organisation. After all, we do not want to over-invest in the anticipatory or reactive capacity if we rarely, if ever, have to deal with disruptive events and thus would never see a return on that investment. However, we should not limit how we think about the impact of that dynamic resilience on our organisation to crises. We can easily apply those 4 basic factors to an organisation’s ability to respond to opportunities. Is a company able to anticipate market trends or other opportunities that present themselves? Can it move fast enough to operationalise those opportunities? Resilient organisations are not only those that can merely react quickly and efficiently to crisis, they are also those that use resilience as a competitive advantage to thrive in the turbulent environment we live in today.

This project was supported by the Flemish Agency for Innovation and Development (VLAIO) – HBC.2020.2504